No safe haven: What it’s like to be a LGBTIQ+ refugee in Malaysia

By Nicole Fong and Rachel Ong | 16 January 2023

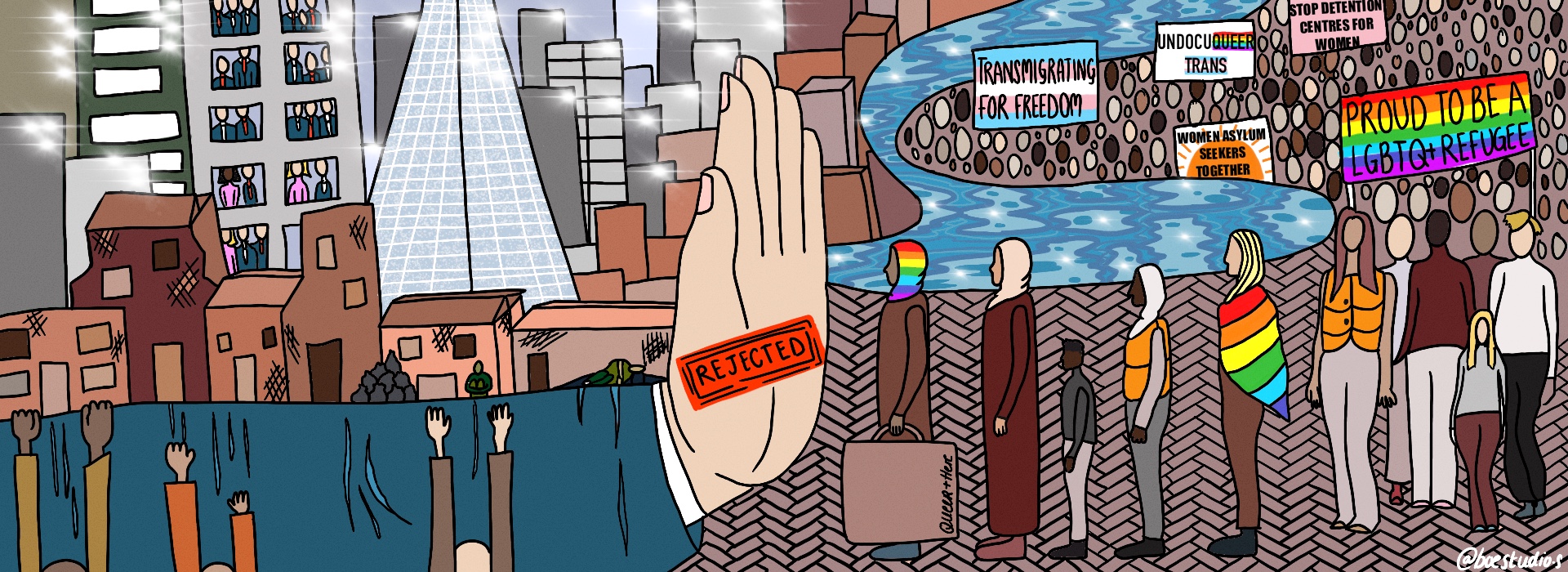

Samiira, a Somali refugee, arrived in Malaysia almost two months ago. As a trans woman, she had to leave Somalia to escape the rampant verbal abuse from her family members and neighbours. Although being away from her home country provides a slight relief, Malaysia isn’t exactly the safest of places for folks like her. Since arriving, she has mostly remained in the confines of her room, leaving only to get daily necessities. Outside, she is not only open to harassment by fellow Somalis living in Malaysia, but also from the Malaysian authorities due to the ‘illegal’ status of refugees and LGBTIQ+ persons in Malaysia.

Samiira is one of 182,780 refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia. Refugees flee their home country because of ethnic or political violence, war or persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, sexual orientation, or gender. For many fleeing from the Middle East and North Africa region, namely Somalia, Yemen, Afghanistan and Palestine, Malaysia is one of the few countries that they can travel to visa-free.

However, the Malaysian government does not legally recognise refugees, rendering them as ‘undocumented migrants’, and placing them at higher risk of arrest, detention, and deportation under immigration laws. It also limits their access to work, education, healthcare, housing, and necessities.

Compounding this, the sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (SOGIE) of LGBTIQ+ refugees puts them in an even more vulnerable position, says Hasan Al-Akraa, a Syrian refugee rights advocate and founder of Refugee Emergency Fund (REF).

Harassment, discrimination, and violence continue

Samiira has escaped her home country, but not the mentality behind the abuse she suffered, which has followed her through the Somali refugee community in Malaysia. She has had to seek separate housing. “If I see any Somali, they abuse me. For what, I don’t know”, she says.

Amir*, a gay Palestinian refugee living in Malaysia, faced death threats and harassment for posting about his sexual orientation on his social media. Although he is physically in another country, he is still unable to be open about his sexuality. “It’s still a bit sensitive for me to post about it on Facebook and Instagram because a lot of refugee community members follow me, who are also Muslim, and they wouldn’t like it”.

To protect themselves while living in Malaysia, LGBTIQ+ refugees have to suppress or hide their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression. As a precaution, Samiira wears more masculine clothing when she goes out.

Esmail, a Yemeni refugee who has been in Malaysia for two years, conceals his gay identity. “It’s difficult, but I have gotten used to it. It’s my life. I have to do it to stay safe.”

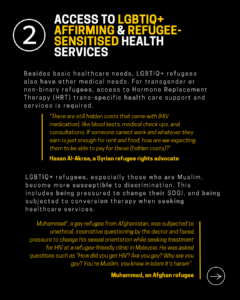

Access to LGBTIQ+ affirming and refugee-sensitised health services

The non-recognition of refugees and LGBTQ persons in Malaysia has a combined effect on LGBTQ+ refugees quality of life. Because of financial constraints, increased stress, and mobility restrictions resulting from the double non-recognition coupled with language barriers and challenges in adapting to the weather, many develop new health issues, malnourishment and aggravation of untreated or pre-existing health issues.

As non-citizens, refugees living with HIV are unable to access government-subsidised life saving treatment. Paying for private care is costly. “There are still hidden costs that come with (HIV medication), like blood tests, medical checkups, and consultations. If someone cannot work and whatever they earn is just enough for rent and food, how are we expecting them to be able to pay for these (hidden costs)?”, says Al-Akraa.

For transgender or non-binary refugees, access to Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), trans-specific healthcare support and services is virtually impossible, at least through legitimate sources.

In Malaysia, where anti-LGBT sentiments in healthcare settings are prevalent, Muslim LGBTIQ+ refugees, face even more discrimination when seeking healthcare, including being pressured to change their SOGI and being subjected to conversion therapy. This discrimination puts potentially life saving treatment and information out of reach.

Muhammad*, a gay refugee from Afghanistan, experienced this while seeking treatment for HIV at a refugee-friendly clinic in Malaysia. He was asked unethical and unprofessional questions like, “How did you get HIV? Are you gay? Why are you gay? You’re Muslim, you know in Islam it’s haram.”

Physically abused by a family member as a teenager for his sexual orientation, Amir* sought help from an UNHCR-provided counsellor, but was instead retraumatised. The counsellor, who was not LGBTIQ+ sensitised, victim-blamed Amir* for the abuse, “You should not disobey him (the family member), you should listen to him. In Islam being LGBT is haram, you should at least acknowledge that.”

As they primarily rely on NGO-run refugee-friendly clinics to access healthcare, there are limited mechanisms available for refugees to lodge a complaint against their healthcare providers. “ On top of having all these legal challenges, you now have to face discrimination and stigma from people who are supposed to be protecting you, people who are supposed to be upholding your dignity,” Hasan says.

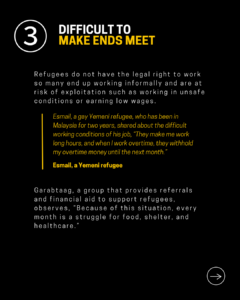

Difficult to make ends meet

Without the legal right to work, many refugees end up in low-paying jobs in the informal job market, exposing them to the risk of exploitation, unsafe working conditions. It has been incredibly difficult for Samiira to find a job so she barely has enough for food and rent.

While Esmail has been able to find work, the situation is exploitative. “They make me work long hours, and when I work overtime, they withhold my overtime money until the next month.”

More support needed

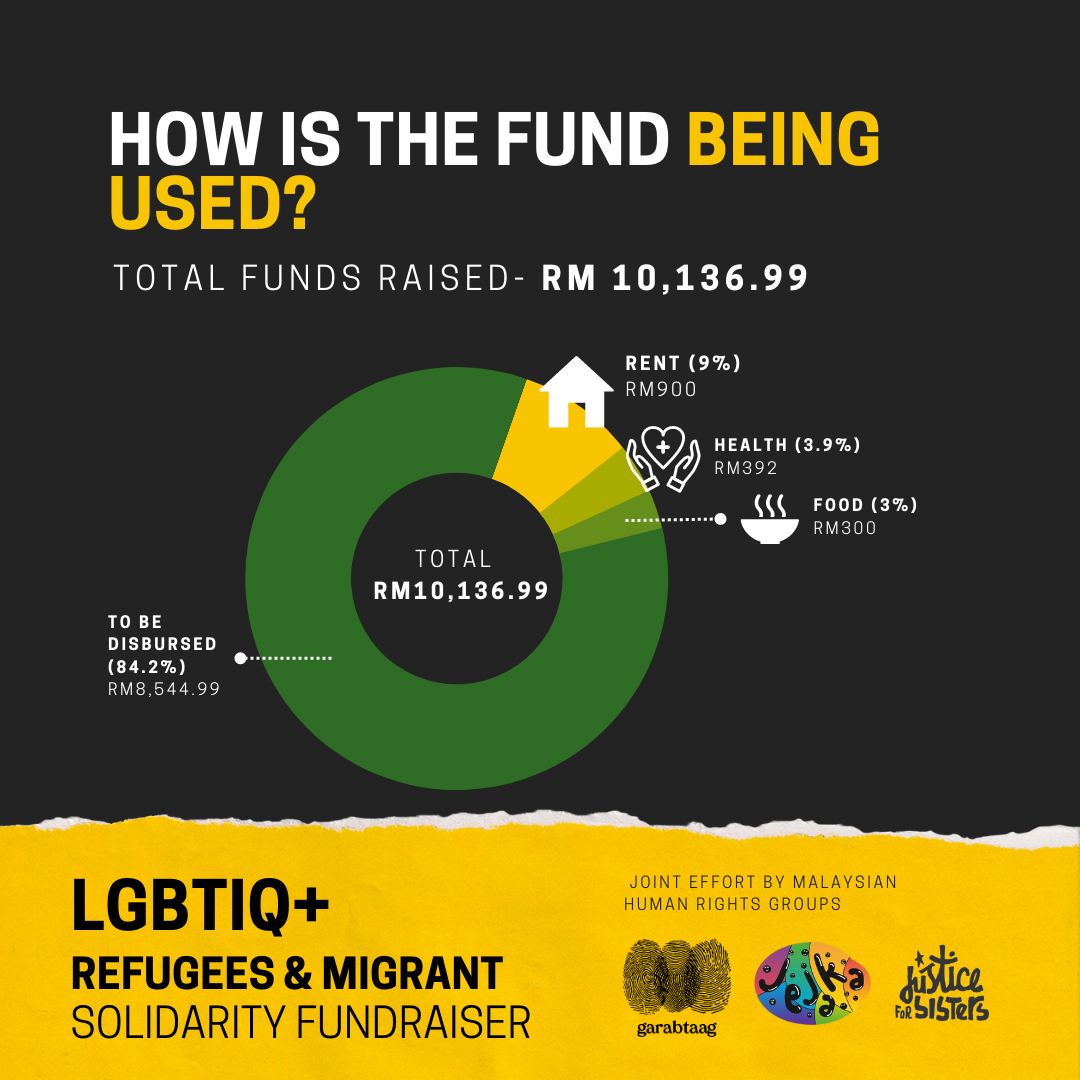

Efforts to raise funds for this community are ongoing, but more support is needed. In December 2022, Garabtaag, Jejaka and Justice for Sisters initiated a solidarity fundraiser for LGBTIQ+ refugees in Malaysia. A total of RM 10,136.99 was raised, reaching just 24% of the RM42,000 target. The funds already collected will go towards covering food and rent for 7 refugees and migrants for one month. Most of them are currently receiving support from Garabtaag. Garabtaag, which initially started as an organisation that provides financial aid for basic services such as rent, food, and healthcare, has since evolved to handle casework, connecting refugees to other service providers.

The Refugee Emergency Fund (REF) is a refugee-led fundraising initiative for emergencies faced by the refugee community in Malaysia. “I started REF because I saw a huge gap in access to secondary healthcare treatments,” Hasan explains. The clinics available for refugees only provide primary care but do not cover any consultation, admission, or treatments in a hospital.

REF is open to all refugees from different nationalities and does not discriminate against LGBTIQ+ refugees. “As long as you identify as a refugee, asylum seeker, stateless person, or undocumented migrant, and you’re faced with an emergency, we will support you,“ Hasan emphasised. They have previously helped LGBTIQ+ refugees who needed financial aid for rent during the pandemic.

What can you do to support LGBTIQ+ refugees & migrants?

Both NGOs rely on public donations to address refugees’ complex and systemic needs. You can show your support by

- donating to their fundraisers directly.

- organising your own fundraisers, food drives, or awareness-raising campaigns.

- helping them develop long-term solutions to support LGBTIQ+ refugees.

You can also learn more and connect with LGBTIQ+ inclusive refugee organisations,

- Refugee Emergency Fund (REF), is a refugee-led fundraising initiative for emergency cases by refugees in Malaysia. You can reach them at refugee.emergencyfund@gmail.com, or on their Facebook and Instagram.

- Garabtaag connects refugees with LGBTIQ+ affirming and refugee-sensitised service providers such as access to HRT or HIV treatment. They can be reached at garabtaag@gmail.com.

*Pseudonyms used to protect individuals’ identity

If you are an LGBTIQ+ person looking to seek asylum or initiate your refugee application in Malaysia, you can apply at UNHCR’s website.

This article was written by Nicole Fong and Rachel Ong. Nicole is a social researcher, human rights defender, and writer working on the intersections between LGBTIQ+ rights, climate justice, and refugee rights. Rachel is an ethnomusicologist doing research in music and gender while occasionally volunteering with Justice for Sisters.